| |

|

|

|

|

|

McCain may well have taken a

page from his opponent’s father, whose own moderate tendencies were

hijacked during the 1992 campaign.

|

|

MCCAIN’S TIRADE against the GOP faithful may have appealed to his

motley coalition of Democrats, independents and insubordinate Republicans,

but it also prompted a question: What sort of strange disease did he have

that would make him say such foolhardy things?

What ails McCain is common among presidential candidates: the curse

of the moderate. It befalls level-headed hopefuls who might fare very well

during a presidential general election, and it can be deadly during the

primary season. Remember Paul Tsongas? Even George Bush the elder got

swamped when he tried to run as a moderate alternative to Ronald Reagan 20

years ago.

In one sense, primaries give

Democrats and Republicans ample opportunity to conduct a process of almost

Darwinian natural selection. As old-time wisdom had it, the candidate who

survived a nominating battle intact presumably was the strongest.

|

|

|

|

|

But this logic has often failed. A candidate who is especially

strong within one party (George McGovern, Michael Dukakis, Bob Dole) can

be equally unpalatable to voters in the other party — or to independents.

Similarly, a maverick like McCain, who has broad general appeal but who

has alienated his own party, will find it pretty darned tough to get

cooperation from local politicians and party officials.

But this logic has often failed. A candidate who is especially

strong within one party (George McGovern, Michael Dukakis, Bob Dole) can

be equally unpalatable to voters in the other party — or to independents.

Similarly, a maverick like McCain, who has broad general appeal but who

has alienated his own party, will find it pretty darned tough to get

cooperation from local politicians and party officials.

In the upside-down world of modern presidential politics, in

which it’s crucial to lure either party’s faithful across to the other

side of the ballot, too much support outside your party can be deadly in

the primaries, and too much support within your own party can be the kiss

of death in November.

ABORTION AS MORAL

WEATHERVANE

Nowhere is this flaw

more visible than in the GOP’s abortion plank: Americans are about evenly

split on the issue of legal abortion (56 percent of Americans feel some

sort of abortion should be considered legal, according to one Gallup

poll), but a large segment of the GOP faithful remain opposed.

Abortion is rarely a decisive

voting issue — only 10 percent of Americans are most concerned with

candidate promises on abortion, according to a January NBC/Wall Street

Journal poll. But it serves as a sort of litmus test, an issue on which a

candidate can test out his moral backbone.

Although the abortion issue resonated for Bush in South Carolina,

the deciding moment in this year’s abortion debate occurred Jan. 20, when

Bush told a group of Iowans that “Roe vs. Wade was a reach.” It was a

defining moment for Bush, a chance to affirm his solid-right credentials

and stake a claim to the conservative mantle.

It was all McCain needed. He took the initiative and exploited the

newly minted system of open primaries in many states, especially New

Hampshire, to turn the battle for the Republican core on its head. For

McCain, it may have been a chance to bring new people — voters sympathetic

to his own disgruntlement with his party — into the Republican

fold.

“If anyone’s sensible about broadening

the party … McCain’s the man,” said Martin Wattenberg, a political

scientist at the University of California, Irvine, and author of “The

Decline of American Political Parties.”

But

McCain’s appeal to those outside his party is balanced by his frequent

alienation of his own party members. As Wattenberg points out: “The

problem is that he’s not presidential in the eyes of the people who know

him,” including his Senate colleagues, only four of whom have endorsed him

— and none of them are on the Commerce Committee, of which he is chairman.

TRAPPED BETWEEN OLD AND NEW

McCain’s coalition building was a brilliant feat, except that he

ended up trapped between the traditional primary system of years past and

a new, untested system that varies so much from state to state that it

barely seems like the same series of political events. His strength came

from his ability to exploit the new, but his defeats have come from an

inability to vanquish the old, and he acknowledged his need to reach out

to his own party’s faithful. |

|

|

|

|

“I have to convince and tell our Republican Party establishment:

It’s great over here. Come on in. Join us,” he told a group of Rotary Club

members in Washington state — before the state’s Republican core rejected

him in the Feb. 29 primary.

“I have to convince and tell our Republican Party establishment:

It’s great over here. Come on in. Join us,” he told a group of Rotary Club

members in Washington state — before the state’s Republican core rejected

him in the Feb. 29 primary.

To the extent

that McCain had support within his party, much of it came from other GOP

mavericks and those who objected to what they saw as strong-arm tactics by

the national Republican Party and the Bush campaign to endorse Bush as the

party’s ordained choice.

“It was a test of

party loyalty,” said Guy Molinari, the longtime borough president of

Staten Island and McCain’s campaign chairman in New York state. “That’s

nonsense. That’s not what politics is about.”

LESSONS LEARNED

FROM 1992

Indeed, McCain may well

have taken a page from his opponent’s father, whose own moderate

tendencies were hijacked during the 1992 campaign as Bill Clinton took

over the middle of the political spectrum. |

|

|

|

|

That year, Bush’s own party may have scrambled his chances during

their national convention in Houston: It was a raucous, unruly affair;

demonstrations by hard-core conservative activists outside the Astrodome

remained a strong symbol that the far right was in control of the party.

This was, after all, the convention during which Pat Buchanan depicted a

“religious war going on in our country for the soul of America.”

That year, Bush’s own party may have scrambled his chances during

their national convention in Houston: It was a raucous, unruly affair;

demonstrations by hard-core conservative activists outside the Astrodome

remained a strong symbol that the far right was in control of the party.

This was, after all, the convention during which Pat Buchanan depicted a

“religious war going on in our country for the soul of America.”

The strident tone may have been an ego boost for the

hard right, but it struck a severe blow to the Bush campaign because it

allowed Bill Clinton to reframe the campaign’s terms, with Bush cast to

the ideological fringe.

McCain now faces

the opposite problem. His appeal is clearly bipartisan, and his success in

attracting crossover Democrats and independents could prove valuable to

the Republicans in the fall campaign.

RIGHT TO MOVE

RIGHT?

Yet that appeal is

precisely what makes McCain so unpalatable to party faithful.

George W. Bush has the opposite problem: By placing

himself firmly to the right of McCain, he gained momentum on the right but

hurt his chances against a Democratic opponent. He has chosen some

emblematic opportunities that seemed politically inastute — first and

foremost his trip to Bob Jones University, which almost derailed him and

forced him to apologize for his behavior. |

|

|

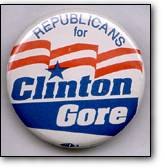

Lest anyone think McCain's

cross-party appeal is revolutionary, the 1992 Clinton campaign crowed

about crossover Republican support, even printing up buttons for renegade

GOP voters to wear.

|

|

“I think they’ve done some other things that weren’t that

bright,” said Lyn Nofziger, a lifelong Republican activist and President

Ronald Reagan’s communications director. “I think what George W. Bush has

to do is get out there and tell people what he stands for. ... He is

hurting himself.”

“I think they’ve done some other things that weren’t that

bright,” said Lyn Nofziger, a lifelong Republican activist and President

Ronald Reagan’s communications director. “I think what George W. Bush has

to do is get out there and tell people what he stands for. ... He is

hurting himself.”

Indeed, this year’s GOP

scuffle has become so raucous that no less an eminence grise than

Bob Dole stepped in before the Virginia primary and told the two hopefuls

to cool the rhetoric.

ANOINTING THE

INDEPENDENTS

Were it not enough

that McCain and Bush are tearing each other asunder, they also must

contend with a primary system — once a stronghold of partisanship — that

has been pried open like a can of cheap sardines.

For example, of all the coming primaries between Tuesday 7 and March

20, including the two Super Tuesdays, only seven primaries — those in

Connecticut, Maine, New York, Wyoming, Florida, Louisiana and Oklahoma —

are closed. The remaining 14 allow some form of cross-party voting.

|

|

|

|

|

Such a muddle makes the independent voter, whose influence seems to

grow with each passing day, ever more important. McCain’s success this

year is based not only on independents but also on his appeal to other

practitioners of political polygamy: the much-coveted Reagan Democrats,

for example, and other party-crossing voting blocs, including the

Republicans for Clinton-Gore who were used to much effect in 1992. All

this cross-pollination may help an outsider like McCain, but it also

drives more traditional pols batty.

Such a muddle makes the independent voter, whose influence seems to

grow with each passing day, ever more important. McCain’s success this

year is based not only on independents but also on his appeal to other

practitioners of political polygamy: the much-coveted Reagan Democrats,

for example, and other party-crossing voting blocs, including the

Republicans for Clinton-Gore who were used to much effect in 1992. All

this cross-pollination may help an outsider like McCain, but it also

drives more traditional pols batty.

LIMITED-TIME

OFFER?

Given the risks, it’s

uncertain whether Democrats and Republicans will allow the open-primary

phenomenon to continue. An open system makes it more difficult for the

parties to activate well-orchestrated local party machines, but it also

offers both parties the chance to open their doors to those who felt

previously unwelcome.

“The Republican

leadership in a lot of states thinks it’s a good thing because it brings

people into your party,” Molinari said. “You may hold on to these people,

and that enriches the Republican Party in the future.”

However, the parties seem aware that the emerging open system

is nothing short of revolutionary, as significant as the last set of

primary reforms in the early 1970s that helped pry power from the clenched

fists of back-room dealmakers. That may not sit well with them.

|

|

|

|

|

McCain, for example, proved effective this season in cracking open

the byzantine New York primary system, but state GOP leaders may bolster

their defenses against any similar attack four years from now.

The future will be decided when Republican National

Committee members sit down at this year’s convention in Philadelphia and

evaluate guidelines for the 2004 primaries. They’ll need to decide whether

open primaries bring in new voters or weaken the party.

“That’s a debate that cuts both ways,” said Tom Yu, a

spokesman for the Republican National Committee. “The national party is

not prepared to come down on either side of that.”

|

|

| |

"Politics" - The critical

issues and debates concerning America

"Politics" - The critical

issues and debates concerning America