Maps matter.

Take a look, for instance, at the beauty of modern Champagne today, and you can fairly argue that its current embrace of terroirs came in large part from the rediscovery of Louis Larmat’s extraordinary 1940s maps. Larmat did what only places like Burgundy were known for doing: depicting the region not as a monolith but as a diversity of small places. And indeed, the current popularity of Burgundy comes in significant part from maps like those of Pitiot and Poupon, which made the climats and terroir concrete and real, something you could hang on your wall.

So why not Beaujolais? In my case, file it under “Everyone needs a hobby.” Or rather, everyone needed a COVID pastime. For me — in addition to bottling dirty martinis for the neighbors — it was a return to mapmaking, namely the cartography skills I’d learned in the early 2000s.

My fascination with Beaujolais was stoked by my work on THE NEW FRENCH WINE, although it’s been there in one form or another for at least two decades. But in the course of my reporting and research, I discovered an entire alternate history of the region — one that undermined its simple reputation and made a clear case for its greatness.

The “bedtime story” version of Beaujolais, as I put it in the book, starts with Philip the Bold banishing “disloyal” gamay in 1395, leading to centuries of ignominy. That’s true on its face, in that his decree was a spark that fueled longstanding tension between the Beaujolais and parts north — not just the heart of Burgundy but the neighboring Mâconnais. Roll forward to the mid-20th century, and Beaujolais reasonably had taken on the countenance of a rustic country hollow.

The past reveals a different tale: Beaujolais was a prosperous region through the 19th century and even into the 20th — producing wines that rivaled Burgundy in quality. (Meantime the Côte d’Or was growing more gamay than pinot noir in the mid-19th century). It was shipping millions of liters of wine both north to Paris — overland, then via the Loire — and south to Lyon.

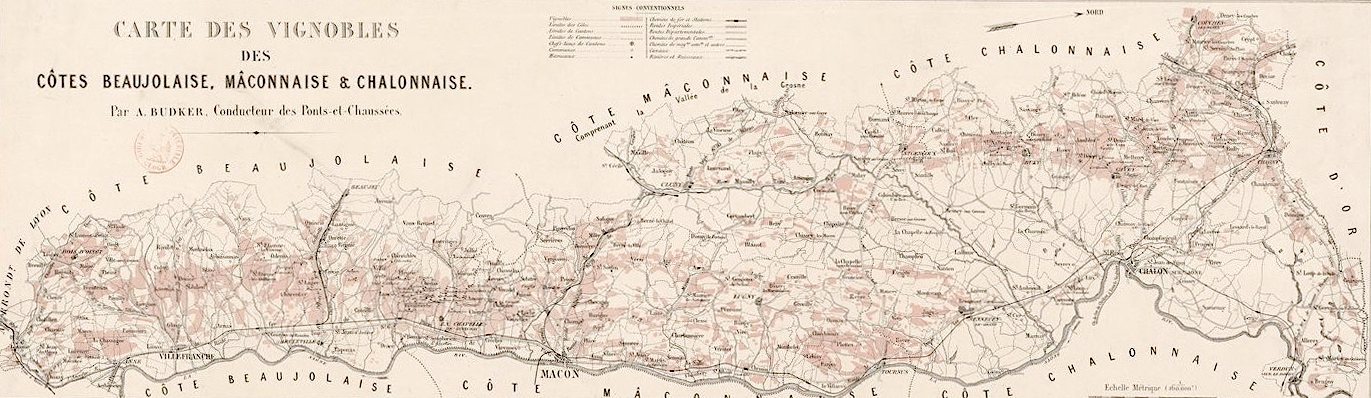

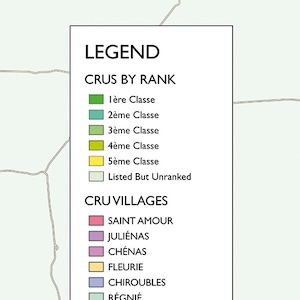

Perhaps the most visible evidence of this wine culture was captured in 1874, when a Lyonnais engineer, Antoine Budker, drafted a map of the Beaujolais (plus the Mâconnais, and Chalonnaise), depicting individual lieux-dits, or crus, ranked in first through fifth place. This work was quietly revolutionary; its methodology mirrored the 1861 classification undertaken by the Beaune agricultural committee, effectively the genesis of the system of crus used today in Burgundy. These classifications not only created a similar hierarchy of quality, but also established Beaujolais as a place worthy of hierarchies as notable as that of Bordeaux in 1855.

Was this a one-off anomaly? It was not. In 1893, Victor Vermorel collaborated with the agronomist Réné Danguy to publish Les Vins du Beaujolais, du Mâconnais, et Châlonnais. Their book ranked hundreds of specific lieux-dits for each of the regions. And Vermorel was no fringe character: He was the most prominent person in Beaujolais at the time — inventor of the portable sulfur sprayer, an industrialist who employed hundreds in his factory in Villefranche-sur-Sâone, one of the region’s most prominent citizens. (His factory would go on to build early automobiles and even an airplane prototype, and he would soon co-author the seven-volume Ampelographie, the definitive reference text on grape varieties for a century.) Vermorel harnessed Budker’s work, and also added local classifications where relevant — C.L. alongside A.B. — to highlight nuances that might have been overlooked by the Mâcon committee. Even amid the destruction of phylloxera, the value of the terroir was clear.

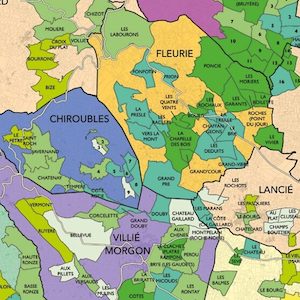

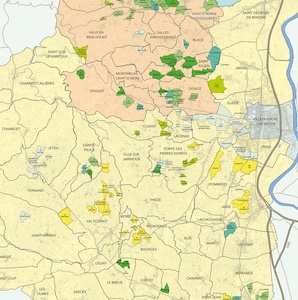

The details in both works are extraordinary — a level of precision not again applied to Beaujolais for more than a century. Yet they affirm some of the things we’ve come to know in recent decades: the importance of places like the Côte du Py in Morgon; Poncié and Chapelle des Bois in Fleurie; Les Capitans in Juliénas.

And they reveal far more: important lieux-dits in the southern Beaujolais, essential terroirs in villages outside the crus, like Vaux and Leynes, and so many other significant places.

It’s telling that these classifications have been rediscovered in the past few years as Beaujolais has reaffirmed itself as a place worthy of precise devotion. But a classification is one thing. To drive home the point, you need a map.

So began “The Classification of Beaujolais” — first transforming these works into viable data, then building a detailed map.

In 2024, I was able to finally find a high-quality printer to reproduce the maps, and thanks to support from a Kickstarter campaign, printed not just the maps but also booklets containing the full dataset. Subsequently I’ve made those available for general purchase via my online shop, as well as via the excellent bookstore Athenaeum, in Beaune.

For more information: